I refer to the period of time following the birth of my first kid as my trial by fire.

New motherhood thrust me into an awkward phase rivaled only by puberty. Three months postpartum, my skin suddenly erupted in deep, sore, bleeding, disfiguring cystic acne that covered my entire face. My hair, once red, curly, and plentiful, turned dark and fell out in handfuls, leaving bald patches not only in the normal spots at the temple but throughout my whole scalp. My whole body seemed to swell, even six months postpartum. That following year, I had two miscarriages. Everything felt as if it were falling apart — because it was!

If one thing unites every postpartum tradition across the world, it is female-to-female care. In case anyone needs reminding: Having a baby is a uniquely female experience.

This unfortunate experience inspired curiosity: What’s wrong with me? Is this normal? Was it always like this? For everyone? How could human civilization sustain itself if every child born means its mother not only endures hell through the pains of birth but also permanent, disfiguring ill health? Where’s the bliss I was promised? What am I missing?

On one hand, maternal sacrifice is built into the very fabric of reality. The built-in difficulty is a fact that must be confronted with fortitude; it also bonds us to our children. But how much is too much? At what point does heroic fortitude become stubborn foolhardiness? At what point is it permissible to look around and wonder if the suffering you endure is the result of some easily remedied ignorance or injustice — and so, warrants a solution? At what point is it permissible to seek help?

At what point is it permissible to seek help? The fact that this question is something I regularly consider reflects how very American I am to the core — proudly! That attitude is what has made America the greatest commercial republic in all of human history.

Ours is an implicitly industrious — liberal, independence-prizing — mode of operation. This doesn’t translate perfectly over to the domestic world, especially not the particular moment in time that is postpartum. It took my health crumbling completely to realize that motherhood wasn’t something I could approach with white-knuckled ambitions of singular success.

“Foolish the doctor who despises the knowledge acquired by the ancients.” — Hippocrates

Today in America, we do not hold any formal, ritualized postpartum tradition. The average American woman is discharged from the hospital within 48 hours of birth, and she is compelled by her employer to return to work after two weeks. The average American family lives far from relatives. The average American neighbor doesn’t know what’s going on next door.

We are more likely to survive than our forebears, but far less likely to continue having children. TikTok is saturated with mom content describing the intense loneliness American women feel in the exile of motherhood. As Tim Carney points out in his recent book, “Family Unfriendly,” neither the infrastructure nor the culture of modern America is conducive to domestic harmony.

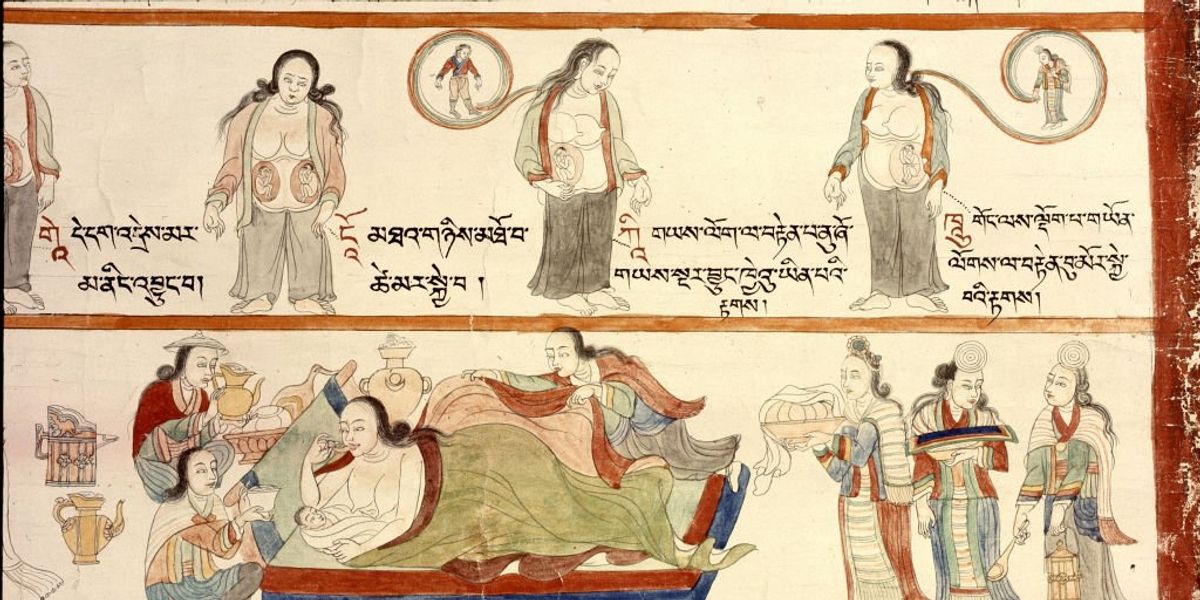

History informs us of alternatives. Contra the modern attitude toward motherhood, childbirth, independence, the nature of the female body, and what matters in life, every civilized pre-industrial society held strict traditional rules — prohibitions and requirements — for women and their relatives to abide by during the period of time following childbirth.

These rules carved out a time and space for mothers and their babies to convalesce, physically and spiritually, for all the ways they were uniquely vulnerable. It was also thought — across cultures! — that the preservation of a woman’s health during postpartum would prefigure good health in menopause.

The medical literature holds that the involution of the uterus after childbirth takes approximately six weeks. This concept is not unlike what is found in the Bible; in the Old Testament, women were considered “impure” for 40 days after the birth of a boy and 80 days after the birth of a girl.

“Impurity,” in this case, is not a matter of spiritual degradation, as the English translation may suggest. It is a matter of ritual separation of human blood from the sanctuary of the temple. A woman bleeds as long as her uterus is returning to normal size. For most women, that means she’s bleeding, or is at risk of hemorrhage, for at least six weeks. Ancient Jews held a ritual “purification” of women 40 days after birth. Early Christians upheld and elaborated on that tradition through what is known now as “the churching of women.”

In “The First Forty Days: The Essential Art of Nourishing the New Mother,” Heng Ou, a Chinese-American mother, describes the ancient Chinese tradition of zuoyuezi, “sitting the month,” where after a baby is born, the mother’s mother, grandmother, or an aunt moves in to nourish her, manage her home, and keep her warm following childbirth.

In Mexico, the traditional cuarentena requires women to avoid cold showers, drink lots of hot soups and milk, wear a postpartum faja, and be fully clothed with pants, socks, and a sweater.

To the Malays, a birth is regarded as a gift bestowed by God. New mothers are often cared for by their mothers or mothers-in-law. During Malay confinement, new mothers will bathe in warm water that has been boiled with lemongrass and ginger to promote circulation in the body. They practice post-natal massage to tighten and tone muscles around the abdomen, revitalize their energy, and improve circulation. The Malays also originated bengkung belly binding, a tradition of wrapping the abdominal muscles to bring the musculature of the waist back together after birth — a practice that has recently become popular in Western crunchy and celebrity circles.

“The march of science and technology does not imply growing intellectual complexity in the lives of most people. It often means the opposite.” — Thomas Sowell

No such acknowledgement of change, of vulnerability, or of status is built into American women’s initiation into motherhood. Modernity — modern technology, including clean water systems, antibiotics, ultrasound, and to an extent, standardized systems of care — enables our historically excellent survival rate. What a luxury that we have forgotten how high infant and maternal mortality has been in the past! But what did modern society exchange, however indirectly or unintentionally, for lower infant and maternal mortality?

Perhaps it was intergenerational interdependence for a sense of certainty. Wisdom for intelligence. Community for commodity. The critical function of midwives, grandmothers, and sisters-in-law — tending vulnerable, familial women and children — has been almost universally outsourced to the medical profession. But the medical profession optimizes for efficiency, reducing the lying-in period to the minimum amount of time necessary to ensure that mom and baby aren’t going to die. That becomes the new standard of care. The tradition of a month of rest became not just optional; it was forgotten entirely. Basic survival is a fine goal — but is it sufficient if our ultimate purpose is to promote true human flourishing? And are the apparent trade-offs we’ve made actually mutually exclusive?

I was lucky, comparatively: There was no office to which I needed to return days postpartum, my husband has always been attentive and loving, and my child and I were both born into an era of maternal and neonatal survival. Still, I suffered as a consequence of chronic sleeplessness, stress, and nutrient deficiency. My symptoms seemed to indicate a chronic inflammation issue that is basically illegible to Western medical professionals.

What was behind the chronic stress? If I can be honest: loneliness, anxiety, ignorance, and stubborn resistance to true rest. Critically, I lacked the company of a more experienced woman to show me the ropes. My birth trauma had convinced me my baby would die if I ever lost sight of her. The internet didn’t help. I hadn’t met my friends yet.

Here is where my Americanness helped me after initially hurting me: Having reached my threshold for suffering, I prayed and resolved that I’d develop a better system for the next time I gave birth, and set forth testing several practices and products cobbled together from the various folk traditions I mentioned already. I asked: What principles of postpartum care are universally recognized?

The regulatory agencies may lag when it comes to innovation, but there are factions of the scientific community that are catching up to the ancestral wisdom by systematically verifying its efficacy. Doctors like Aviva Romm have inspired a new generation of practitioners to take herbal medicine seriously, and the studies coming out about the effectiveness of herbs such as holy basil, used in common folk postpartum care are promising. Discovering Dr. Romm was life-changing.

The following postpartum principles helped me not only maintain but improve my health, sanity, hair, and skin after my second and third children were born. It’s never been easy, but never again did I experience the cold exile of isolation, exhaustion, hormonal chaos, and depression that haunted the first year of my first daughter’s life. These are where I’d start if I could go back in time. I hope they help you, too.

Female Friendship

“A woman’s function is laborious, but because it is gigantic, not because it is minute. I will pity Mrs. Jones for the hugeness of her task; I will never pity her for its smallness.” — G.K. Chesterton

If one thing unites every postpartum tradition across the world, it is female-to-female care. In case anyone needs reminding: Having a baby is a uniquely female experience. Husbands should be intensely interested and supportive of their wives’ needs, but there are things they cannot know and solutions they cannot intuit because of the limitations of their experience. In so many ways, postpartum begins a new season of formation, and you will need a teacher.

Find female friends. Find surrogate (not literally) mothers if yours doesn’t live nearby or is otherwise disposed. If you’re expecting, new to a place, and you have the money, invest in a postpartum doula, night nurse, or mother’s helper. There are some apps now, including Peanut, where you can search to meet buddies, but I think the best kind of friendships happen when you cannot choose your precise qualifications for what you think you like in someone.

Church communities often (not always) provide some kind of preformed social connections — and a shared worldview upon which new connections can be forged. Hobby groups can’t guarantee ideological uniformity, but participation in one at least signifies that the participant values the human experience more than scrolling TikTok endlessly in their spare time — that’s a red pill of its own.

Crunchy Facebook mom groups may be another good place to go spelunking for friends. Start your own group message and let people know when you’re heading to the gym or the park or wherever. The key is to tap into and make yourself useful within existing networks of women; even if you don’t find your bestie on the first shot, you will learn more about what, and who, is out there. If your efforts are fruitful, these will be the women that talk you through dark days, bring you food, babysit your kids, become godparents to your kids, and watch your kids grow up. Love them well.

Seclusion, not isolation

“We live, in fact, in a world starved for solitude, silence, and private: and therefore starved for meditation and true friendship.” — C. S. Lewis

“Bouncing back” — the vapid expectation that women “be back in their pre-pregnancy jeans” within the month — is mirrored by the expectation that immediately after the pains of childbirth have passed, the new mother is as emotionally and mentally sharp as ever. Clinical postpartum depression and anxiety aside, this is an amazingly ignorant expectation, and it requires its witting or unwitting believers to also believe the “mind in a vat” account of human nature: The mind and body are easily and completely distinguishable, the latter easily overcome by the former.

Historically speaking, postpartum convalescence was about much more than the body, since the body was never understood as totally distinct from the mind. In order to protect one’s peace, new mothers should remain sequestered from strangers, outsiders, and, truly, anyone they do not trust.

Even some traditionalist circles seem to do progressivism with extra steps in this regard, with some women returning to Latin mass within 48 hours of giving birth. Recovery is not a competition. Though it’s rarely articulated and difficult to dig up historically, there is a robust tradition of postpartum rest for Christian mothers. Do not allow yourself to be made to feel guilty or extravagant for taking your forty days of seclusion if you can arrange your life in such a way that it’s possible.

Warmth

Another simple and universal truth of traditional postpartum care: for the full forty days, keep your body warm, especially your feet and belly. Wear wool socks. Never be without a blanket. Warm baths with herbs, epsom salts, regular salt, baking soda, and lavender essential oil can be lifegiving. If you get your hair wet, dry immediately with heat. I use a heating pad over the uterus which also helps with afterbirth pains.

Vitamin A is for Animal

“Let food be your medicine and medicine be your food.” — Hippocrates

Breastmilk is extremely high in vitamin A, a vitamin that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has made a point to fearmonger against because isotretinoin (a highly concentrated form of synthetic Vitamin A, sold commercially as Accutane) is teratogenic to fetuses in utero.

Generally speaking, the rules ACOG sets for pregnancy are meant to be followed postpartum. Out of an “abundance of caution,” doctors instruct nervous new moms to avoid Vitamin A. Don’t eat liver, they say; too much Vitamin A could cause birth defects. While the latter part of that statement may be strictly true, it is an embellishment bordering on a lie, the consequences of which are staggering and, though not as obviously harmful as extreme birth defects, still painful.

Dr. Weston A. Price, a dentist who studied the bone structure of indigenous versus industrial peoples in the 1930s, concluded that modern people’s abandonment of Vitamin A-rich animal protein such as organ meats has led to underdeveloped jaws, crooked teeth, and breathing issues due to structural abnormalities in the modern face.

Price discovered that the diets of healthy traditional peoples contained at least 10 times as much vitamin A as the American diet of his day. His work revealed that vitamin A is one of several fat-soluble activators present only in animal fats and necessary for the assimilation of minerals in the diet.

For the pregnant and postpartum mom, vitamin A deficiency can look like cystic acne, low progesterone, and immune issues.

TLDR: you need to be consuming animal products. Every ancient tradition of postpartum care abides by this principle, leaning heavily into animal proteins and fats. Raw milk is preferable because the pasteurization process removes most of the Vitamin A and enzymes from the product. Organ meats are great. You can take the liver in capsule form. Steak is great. Chicken and bone broth are great. I put gelatin in everywhere it can dissolve without detection. In my experience, animal proteins are the nutritional necessity for postpartum. No vegan diets allowed.

Rest and Prayer

God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.

If you haven’t already downloaded the Hallow app, it may be a good investment for your transition from maiden to mother. There are times when the exhaustion, the frequent interruptions, and the general sense of spontaneity will interrupt all your best laid plans for a 15-minute meditative prayer. “For everything there is a season, a time for every activity under heaven. A time to be born and a time to die. A time to plant and a time to harvest.” (Ecclesiastes 3:1-2)This is a time to be born; when a baby is born, so is a mother. You may need to relearn how prayer happens throughout the day. You may learn what it really means to pray without ceasing. Hallow can help.

So many of the postpartum traditions I explored were inherited from a pre-Christian culture where a certain amount of superstition about protecting the baby from things like “the evil eye” was baked in. I think the truth in that impulse is that a woman can be as spiritually vulnerable as she is physically and emotionally in the days following childbirth.

I think it’s good practice to simply acknowledge this. You will power through by God’s grace, but acknowledge it. Acknowledge your need for rest, and understand that Christ invites us to rest, to abide in Him. We have to do that, even if we’ve been trained by the careerist culture never to flinch or take a break. We women especially have some things to unlearn here. It’s important to remember that we have a God-given female body and vocation to honor and uphold.