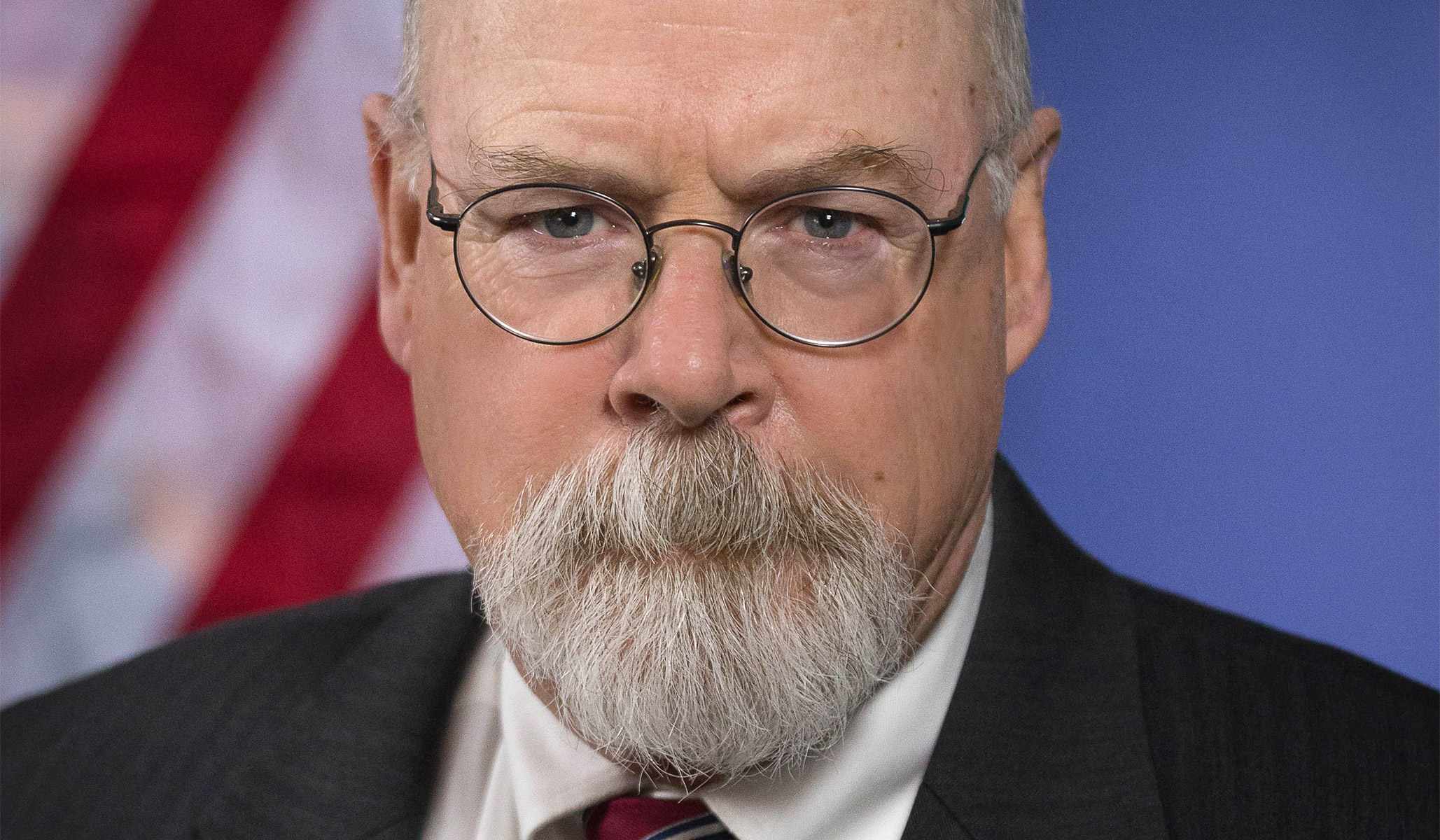

David is right on the money regarding special counsel John Durham’s most recent court submission — which, it should be noted, is a response to a motion by the defense, not a response to media coverage, much less a retreat in the face of media coverage.

As the Durham probe has crept along, often with nary a peep out of the prosecutor’s office for month after month, with Democrats complaining that he was wasting resources and Trump supporters squawking that he was asleep at the switch, it has been apparent that Durham does not perceive it as his job to feed the media beast. He did not file a motion with the court because he thought it was a slow news day.

As Rich and I discussed this morning while recording the recently posted TMR podcast, there are always specific, case-related reasons why prosecutors make pretrial court submissions that proffer sundry details about what they will seek to prove at trial. These reasons relate not to what the public is curious about, but to whatever the submission in question is asking the judge to do (if it is a government motion), or to respond to whatever a defense motion has asked the judge to do. As a result, the prosecutor’s sense of the proffered information’s relevance is likely to be very different from what seems relevant to journalists and partisans (some of the former are also the latter). The prosecutor’s understanding of the information he proffers — both of its nature and how it relates to other information that is germane to the case but not discussed in the submission — is also apt to be better informed than that of commentators. That’s not because the commentators are partisans or morons (though some are); it’s because the investigator always knows things we don’t, is always aware of details that for us are gaps in need of filling.

In this instance, Durham filed a motion last week asking the presiding judge, Christopher R. “Casey” Cooper, to inquire into a potential conflict of interest borne by Latham & Watkins, the law firm representing defendant Michael Sussmann.

L&W also represents (or at least has represented and thus, under ethical rules, owes continuing fealty to) (a) Perkins-Coie, the law firm at which Sussmann worked during the pertinent time frame (including in connection with Sussmann’s representation of the Democratic National Committee and tech executive Rodney Joffe), and (b) Marc Elias, Sussmann’s law partner at the time (and the principal partner in Perkins-Coie’s representation of the Hillary Clinton campaign). For the most part, Durham’s motion adheres to Justice Department convention of not naming uncharged persons and entities: Perkins-Coie is “Law Firm-1,” Elias is “Campaign Lawyer-1,” Joffe is “Tech Executive-1,” and the DNC is “Political Organization-1.” (The Clinton campaign is referred to by name because it pervades the case — it would be impractical to avoid referring to it by name.)

Prosecutors are duty bound, under court precedents, to raise any potential conflicts involving defense counsel of which they become aware. It’s easy to understand why. A lawyer, for example, is not permitted to cross-examine a current or former client. So, let’s say Lawyer A is representing the defendant, and a former client of Lawyer A ends up becoming a critical witness in the trial. This is a conflict for Lawyer A because he owes the defendant zealous representation, but ethics rules forbid him from cross-examining (or even making jury arguments against) the witness, his former client. Thus, the defendant could be deprived of the constitutional rights to confront witnesses, present a defense, and have effective assistance of counsel. That would cause a mistrial, an enormous waste of resources.

Ergo, conflicts get resolved pretrial. Most often (because we try to preserve a defendant’s choice of counsel), this is done by allowing the defendant to waive the right to cross-examine a potential witness. Sometimes, a court will instead ensure that a non-conflicted lawyer is on the defense team to handle the questioning of, and arguments about, any witnesses as to whom there is a conflict. But sometimes, if the conflict is serious enough (the lawyer cannot confront the main witnesses in the case) or complex enough (it gets very hard to predict all the things that could go wrong in multiple-representation situations), defense counsel must be disqualified from the case, and the defendant must obtain new, non-conflicted representation.

Here, Durham (who related the applicable law on this subject at pages 5–6 of his motion) has opined that the potential conflicts can probably be addressed by a waiver. And we should stress: To flag a conflict is not to accuse anyone of misconduct; it is to address a contingency lest it become a huge problem.

In order for a judge to understand why there is a conflict, the prosecutor must foreshadow what the evidence will prove. This enables the judge to grasp why the testimony of possible witnesses who are current or former clients of defense counsel matters to the case. That is why Durham had to proffer parts of his case that bear on Perkins-Coie and Elias. If Sussmann is to be permitted to keep L&W as his trial counsel, he must waive the right to claim prejudice from any potential conflict his L&W lawyers have.

Under Supreme Court precedents, waivers involving constitutional rights must be knowing and voluntary. In the potential-conflict situation, then, the judge must make a record that the defendant was fully informed about the potential conflict, and made an uncoerced decision that keeping his potentially conflicted lawyer was worth forfeiting the right to claim harm from the conflict. To do that, the judge must walk the defendant through the evidence that bears on the conflict, and make sure the defendant understands how his interest in challenging that evidence could be harmed by the lawyer’s conflicting loyalties. The judge cannot do that unless the prosecutor has explained what that evidence is.

That is why Durham said what he said. Pace Mrs. Clinton and her sympathetic scribes, it was not a “right-wing lie.” It was the execution of a constitutional and professional obligation.